The Creative Life, Again

This week I celebrate the solstice with a few images and reflections about my activity of the past two months. I have been engaged in three related but distinct activities: 1. transforming a 1952 garage into a studio with Rick Fitzgerald, a wonderful carpenter; 2. beginning to work on a series of studies on the theme of "path"; and 3. revising my 2003 book Art Lessons.

1. Creating a new studio: helping Rick put up the "rock" after closed cell insulation was blown into the floor, walls, and ceiling of the ramshackle old garage.

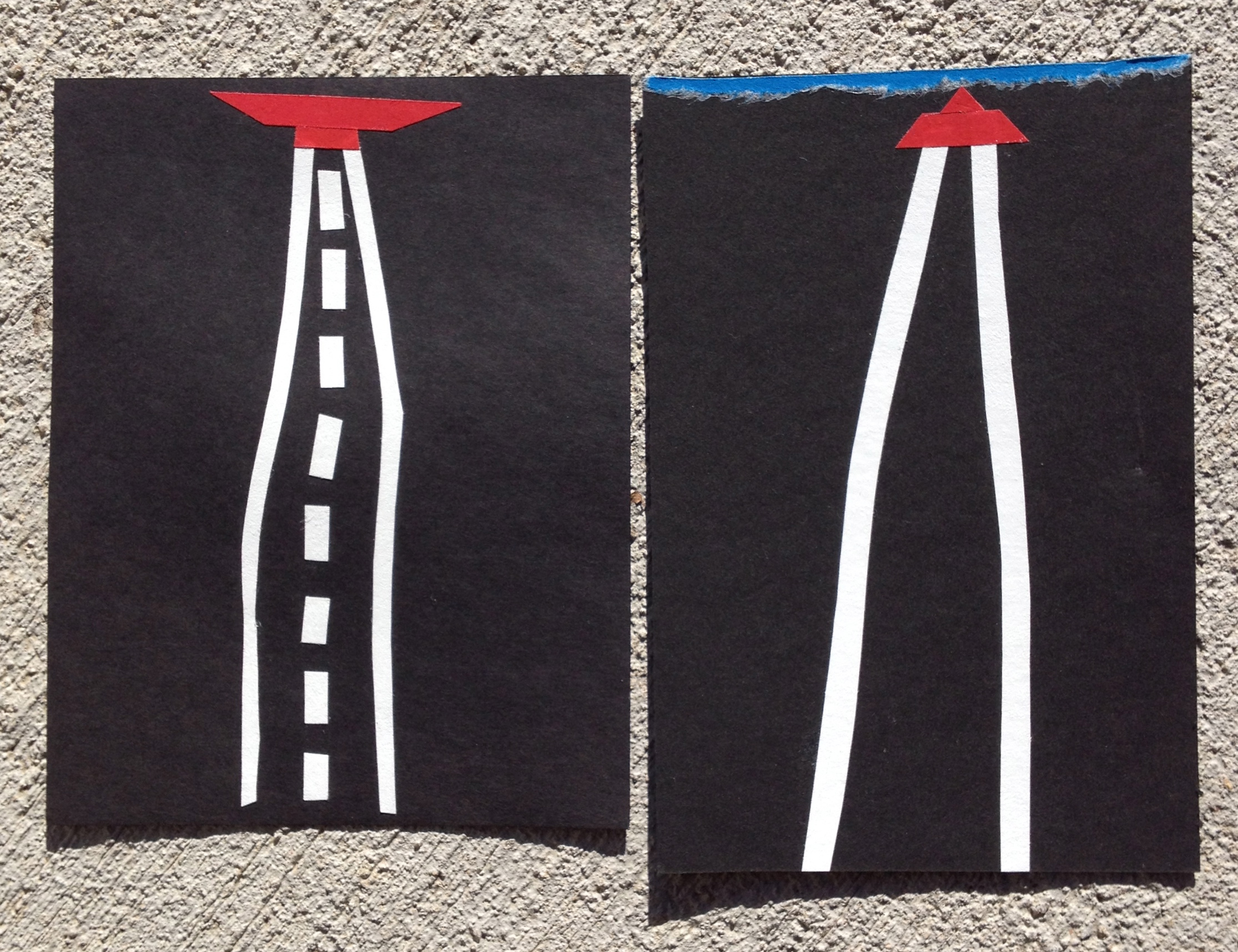

2. First studies of "path," a new series of mixed media works on paper. These are small, each c. 4" x 6".

3. A preview of my latest book, Art and American Buddhism: An Artist’s View. I plan to send the manuscript to a publisher for review around the beginning of February 2015.

Abridged “Preface”

I begin with a simple task: to explain what the title of this book, Art and American Buddhism: An Artist’s View means. Here, in the Preface, I invite you, the reader, to enter into an inquiry with me. Each word in this title expresses a particular aspect of book’s central purposes; and each word is vast in its implications and meanings.

ART. Derived from the Latin ars, skill or craft, art is an especially multivalent word. It names human activity in the world, often contrasted with the natural world, nature. We generally associate it with the creation of beauty, but art can also be grotesque, ugly, or even violent. The word names our activity of building and constructing with physical materials, but also with sound, color, movement, and language. I believe that making and looking at art can be a form of contemplative practice, a space in our noisy and information-saturated lives for solitude, silence, and being in the present. Like prayer and formal meditation, art can become part of the foundation of who you are in the world, as intrinsic to your nature as breathing. Here, my focus is the visual arts.

AND. The word “and” is a conjunction that identifies a particular kind of link between art and American Buddhism. In this book I seek to show the interdependence of these two topics. This book is about artistic formation and aspiration: about how you might become an artist, about what it means to be an artist, and about how to sustain an artistic vocation. It is episodic, divided into loosely connected chapters, each of which addresses a particular topic. The chapters do not focus mainly on the acquisition of technical skills in particular media or on the art of particular artists. Using stories drawn from my life, as well as historical and philosophical content, each lesson seeks to speak to you, the reader, across personal differences and toward shared insights and experiences. The questions that grip me are big questions—what philosophers call the ultimate questions. I do not believe in universal truths, but I do believe that the truths of one life may illuminate another.

AMERICAN. In each cultural context where it has been embraced by humans with unique languages, customs, histories, and traditions, Buddhism has transmogrified. And, in the American context, Buddhism is changing. You may encounter Buddhist teaching in traditional manifestations, such as the Longchen Nyingtik lineage taught by the Venerable Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche and practiced within the Mangala Shri Bhuti sangha. Or, you may encounter Buddhist forms that are stripped of all religious structures and overtones, morphed into generalized mindfulness practices within secular institutions such as the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society, The Mindfulness Institute, and Buddhist Geeks. In short, some teachers and Buddhist communities are deeply committed to maintaining traditional forms, while others seek to adapt those forms to the secular American context. Plus, there is the American consumer ethos, about which I will have more to say intermittently in this book. My own Buddhist path reflects some distinctly “American” characteristics: an exploratory spirit, coupled with an interest in tradition and history. Having read widely about Buddhist lineages and traditions, having practiced within Zen Buddhist, Vipassana, and Vajrayana communities, and having taught about Buddhist arts to both large university lecture classes and small undergraduate and graduate seminars, I still consider myself a beginner.

BUDDHISM. And this gets me into the question of what Buddhism refers to in the book’s title. Shunryu Suzuki begins his brilliant book, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, with a prologue about what it means to be a beginner. To be a beginner means always to be “ready for anything . . . open to everything.” The beginner’s mind is not closed, but contains many possibilities. It discriminates, but not too much or too often. It is not demanding and greedy. It waits. It is not concerned with attainment and achievement. It is compassionate and boundless. Suzuki Roshi reminds us that this spirit of always being a beginner is the “real secret” of all of the arts. I share his view. I feel it is important to begin by acknowledging my standpoint here, because I am neither a Buddhist scholar nor did I grow up in a Buddhist culture or household. What I have to say comes from my study and practice over many years; others, of course, might describe Buddhism differently, but this book reflects what I understand.

Buddhism is not founded on belief or faith in a figure or god, but on direct experience. In this sense Buddhism is a path of self-reflection, of looking without bias or judgment at what arises in our perception and experience, thoughts and feelings. Its foundation is the historical Buddha’s teaching on the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. In all of its cultural manifestations, Buddhism is grounded in the view that all sentient beings desire happiness and freedom from suffering. We suffer in so many ways, but especially from our ignorance, greed, and hatred. Based on fundamental values of altruism and kindness, it is a path of finding out for oneself, through study, practice, and service, how to live and how to prepare for death. All Buddhist forms share concepts of “no self,” the goal of enlightenment for oneself and for others, and karma and reincarnation. Buddhism is thus both a philosophy of life and a practical path, a set of techniques, for attaining the goal of enlightenment.

AN. The subtitle, An Artist’s View, begins with the modest assertion that I do not claim to speak to you about all of Buddhism, about all forms of art, or about all possible artistic goals and objectives. This book is a personal statement, born from my experience as a practicing artist, writer, and teacher, who has practiced and studied Buddhism for a long time. I know that there are other competing views and values about art, about the artist, about the relationship of art and life.

ARTIST’S. My personal journey has been circuitous. I began my adult life studying to become an artist. Then, as a result of my scholarly study, I became a philosopher of art. Or, as one of my mentors, M. C. Richards, once said to me, perhaps my work in the world involves defining the vocation of the artist, for myself and others. This has proven to be a prescient comment. At this point in my life, I seek to incorporate verbal and visual languages in my creative and written work, to explore and expand upon the meaning of vocation or calling, and to integrate my artistic and Buddhist practices. Art and American Buddhism reflects this intention.

VIEW. Art and American Buddhism: An Artist’s View is structured around three major themes: cultivating spirit, forming a mind, and disciplining the body. I begin with the inner life, because I believe that this is the foundation for everything. The chapters of the first section, Cultivating Spirit, address the inner psychological and spiritual life. The second part of the book, Forming a Mind, deals with the intellectual formation of the artist. How does one become an artist? How does the world of ideas intersect with and help to shape what you create? The book's third major section, Disciplining the Body, plays on the nuances of the word “discipline.” This section of the book examines the meaning of self-discipline for the artist, as well as ways in which creative work, meditation, and various technologies literally discipline and form the body.

_____________________________________

Always more to say, but I've got to get to work! I wish you, the reader, a fine end of 2014 and beginning of 2015!