The Story of a Chair

Sisters Sanctuary in winter 2009, photo by Valari Jack

Sisters Sanctuary in winter 2009, photo by Valari Jack

We are now in our fifth month since the September flood that devastated Jamestown and wreaked havoc at our place, completely destroying the one-acre site. Repair of the house and garage continues because of the dedicated work of our friend Quinter Fike and a host of others. Costs escalate, but we are determined to make the two remaining structures habitable again.

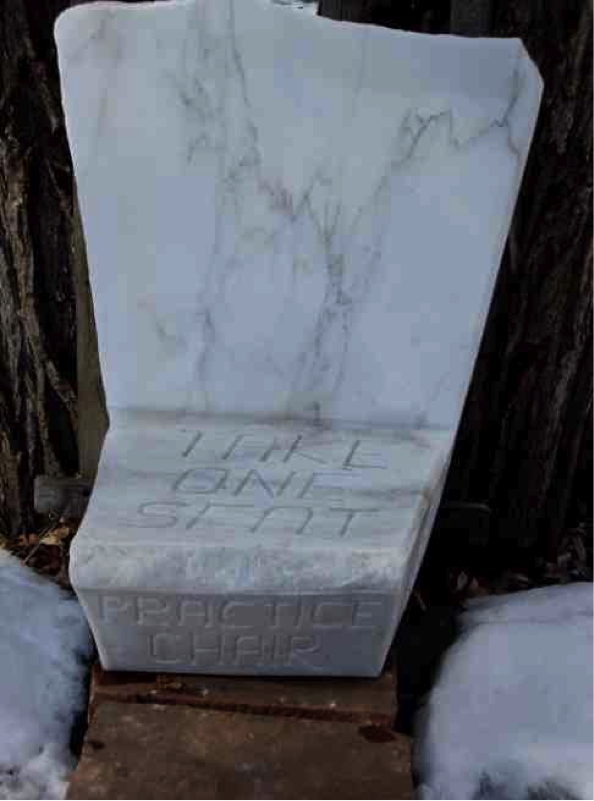

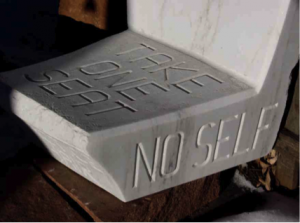

This past week my grief resurfaced with a flood-like force, focused on a stone that I carved in 2007. The 38-inch-tall marble Practice Chair rested on a steatite base in The Sisters outdoor sanctuary—so named for its grouping of nine tall willows. Four of the chair’s faces were carved with text. The seat of the chair read "take one seat" and the front announced its title. The back of the chair was highly polished, with glittering gold veins. The reverse side of the upright back remained rough, displaying the outline of a snake. I thought of this snake as the naga spirit that resided inside.

From the time I carved it, the chair’s title had two meanings. First, this chair was to be a maquette or model for a larger chair that I would carve. In this sense, Practice Chair provided me with practice in making a chair. Second, the chair functioned as a place for practice, a seat on which to undertake meditation. In every season I regularly sat there to observe the world, and my mind.

Although I would sometimes place a piece of wood on the seat for warmth, I never forgot that I was sitting on “take one seat.” The sheer physical presence of these letters seemed to offer a counterpoint to my felt sense of groundlessness and awareness of impermanence. To take one seat means being willing to sit down, focus on the breath, and encounter oneself on a regular basis. It means choosing one discipline from among the many distinct spiritual practices of various traditions. It means, more than anything else, being present, practicing.

As an artist I, too, take a seat. In order to find a seat, a method of working that suits me, I have had to explore. Our consumer culture makes it exceedingly easy to shop around; and we are encouraged to try this and try that. It is tempting to make this eternal process of trying the new into a permanent way of working. But regardless of how one learns about the range of meditative practices or about the range of materials and techniques in the visual arts, eventually one must ask, okay, now what? This is the time for taking one's seat, for settling into the process of finding the most appropriate form for one's contemplative and creative practice. The chair functioned as a continuous source of inspiration for my meditation and studio work.

Perching on Practice Chair, my right hand would caress the word "emptiness" while my left fingers traced the letters of "no self." The word emptiness articulates a profound idea that is at the core of Buddhist teachings. It means, simply, that nothing has or carries intrinsic existence. Everything in the universe—persons, events, nature itself—originates through co-dependent causes and conditions. Every life is the result of thoroughly interrelated conditions that give rise to the uniqueness of that life's expression in each moment. The same principle applies to the self: there is no singular and permanent self. All aspects of the self—the body, one's experience, and even thought itself—all arise through interdependent processes. I believe that we study the self in order to forget the self. Forgetting the self and giving up my self-importance, even momentarily, I could become simply one of the ten thousand things of the phenomenal world.

Debris among the Sisters,

Debris among the Sisters,

photo by Catherine Haynes, October 2013

Today, the nine willows that defined the outdoor sanctuary remain crusted with mud. Although we have tried to dig out much of it, debris still fills some of the spaces between them. The sandstone floor is gone, as are the huge boulders that defined the boundary around the trees. Practice Chair “went downstream,” as did so many others of my marble texts and sculptures.

Shaking and wailing, I commented to my friend Jennie that I should be smiling through my tears, too. Who could fail to notice that the very meanings I assigned to the chair contain lessons I must learn about ego, attachment, and loss?